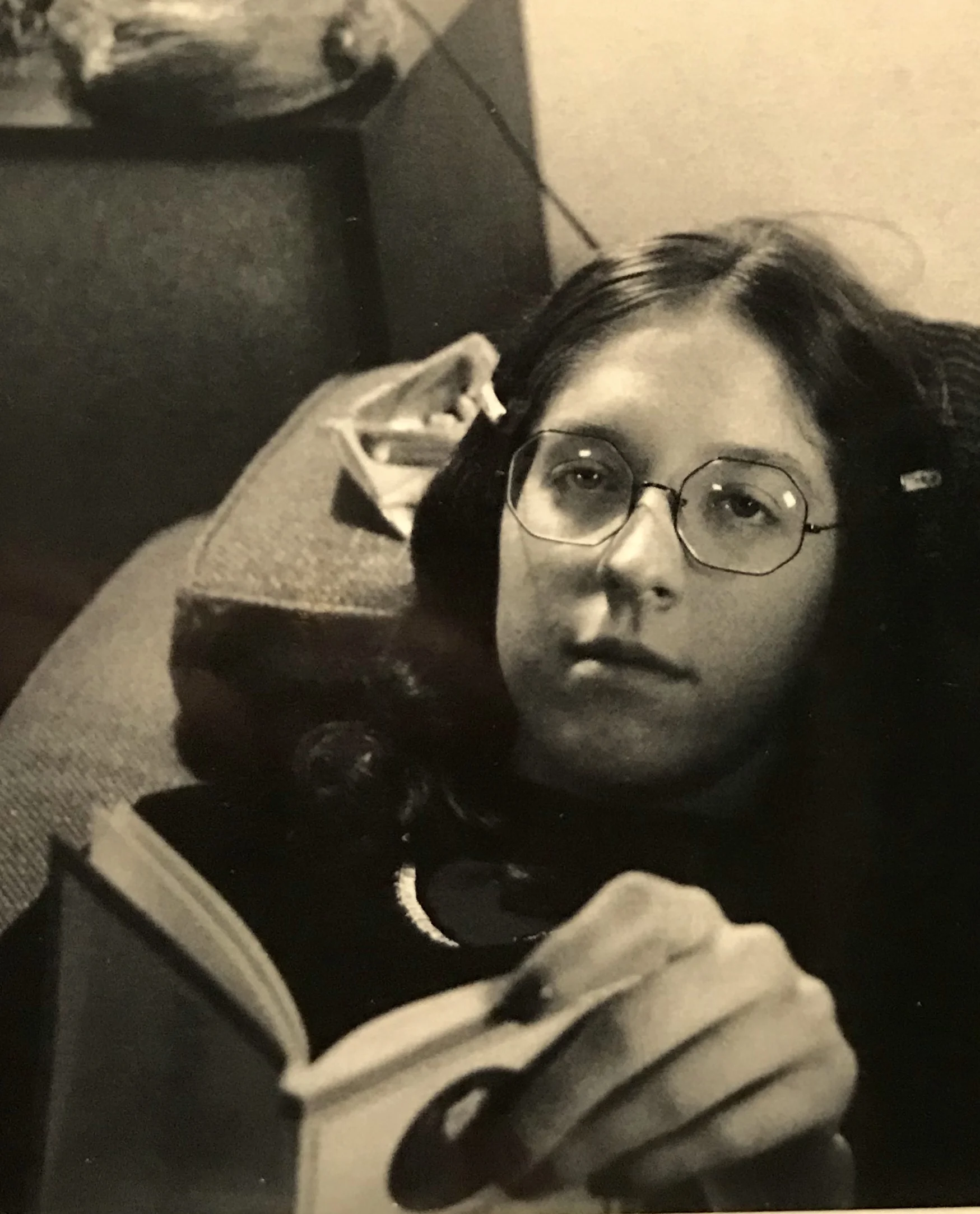

By the time I left for Africa, my life had stagnated—a scary thing when you’re only twenty-four. My friends were all moving away, settling into committed relationships while pursuing careers as therapists, lawyers, and stained-glass artists. In the meantime, I was stuck in a rundown bungalow in Knoxville, Tennessee, teaching psychiatric patients to make tile trivets and then going home to smoke pot with my cat.

I felt invisible to my family and friends, and increasingly, to myself. So I joined the Peace Corps—something I’d been dreaming about since I was a teenager—and went to The Gambia, a small country in West Africa. I was no longer the ear into which my parents and friends poured their personal problems. I was getting to know people from all over the world, and I was as exotic to them as they were to me.

I also met the man I would marry, now my husband of almost four decades. Tom left Poland in the mid-70s, when the Communist party made it hard to get out. I saw him as a romantic hero, a man without a country who’d fled a broken marriage and a repressive regime. In his eyes, I shone with the glamour of the West, the land of free speech, pop culture, and fast cars. I admired his work as a pediatrician in the Gambian capital, and he admired mine as a community organizer in a small village. We couldn’t take our eyes off each other.

We got married in The Gambia, and three years after coming to the States, he became an American citizen.

Years passed, then decades. Without meaning to, we took our intimate knowledge of each other and set it in stone. This immutable shorthand saved a lot of time and energy, but it also created a problem: Once something is set in stone, it’s hard to change. Once we think know another person, we stop looking and asking questions. I’ve sometimes felt so unseen by my husband, the man who once couldn’t take his eyes off of me, that I’ve wanted to run away from home and start all over again, like I did in my mid-twenties.

Instead, I’ve done what I can (sometimes clumsily) to make myself seen and heard. This has led to conflict that took a long time to resolve; but since the conflict was already there, I figured I might as well put it out in the open where it could be dealt with. Whenever we did this, our marriage would reach a new homeostasis—then we would revert to our familiar shorthand, setting our knowledge of each other in stone.

This wasn’t necessarily bad, as long as we remembered to look at each other more closely every now and then. As we settled our most stubborn differences, (at least as much as they’ll ever be settled), our life got calmer. Ironically, this lulled us into thinking we didn’t need to pay close attention anymore. After all, life was great. Great, but lacking surprise. So when Valentine’s Day rolled around this year, I suggested we give each other a present with a $20 spending limit. We usually do dinner and flowers, but I wanted us to come up with something less formulaic, something that would make us pay attention.

Tom agreed to the plan, though he sweats gifts. He uses his powers of concentration for diagnosing sick kids and predicting the trajectory of tennis balls, not for making a mental note every time I mention some small object that has caught my fancy.

I knew exactly what I would get him—which isn’t to imply that I always see him with 20/20 vision. It’s just that a few weeks earlier, he announced that the terrycloth headbands he’s always worn to play tennis are dorky. At seventy-five, he wants to switch to bandanas folded into headbands, like super-star Rafael Nadal wears. Tom would never go to the trouble of buying bandanas for himself—that would be paying too much attention to fashion, which, to the generation of hero-obsessed Polish men born around WWII, is as uncool as driving at dusk with the headlights on.