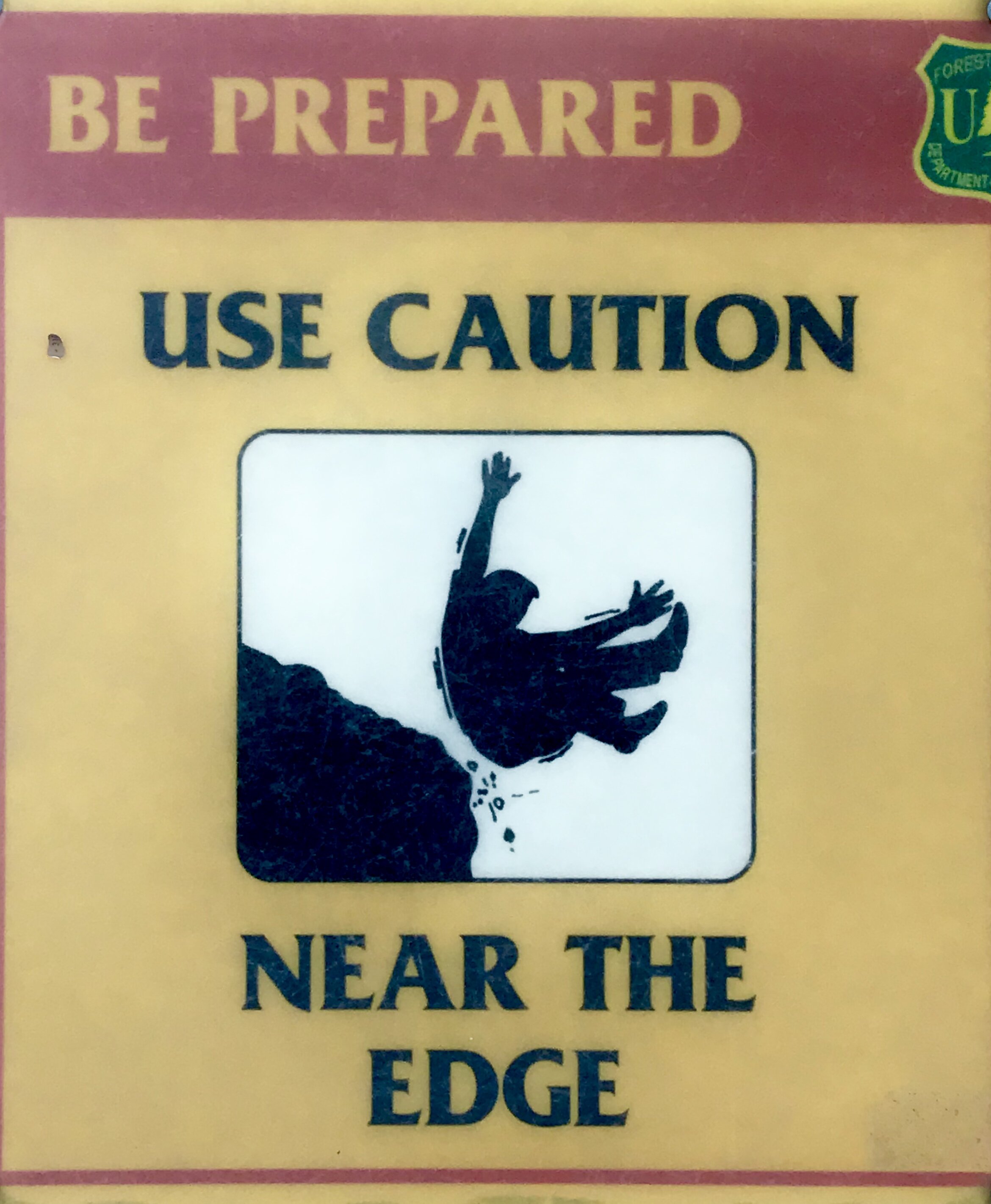

If you fall off your horse, you’re supposed to get back on as soon as you can. The longer you wait, the more firmly fear or plain old inertia sets in. The pandemic stopped my writing in its tracks. I launched this blog to reflect on the themes I explored in my memoir, The Mango Garden: leaving home, taking risks, embracing the unknown and being changed by it. Now, as if worrying about jet blasts, monster waves, and hard falls weren’t enough—(I love documenting warning signs when traveling)—we have to think about Covid-19 every time we walk out the door.

When I get stuck in my writing, unable to find the right word or unsure about what I’m trying to say, I get up and do something with my hands, usually cooking. My mind relaxes and nine times out of ten, the answer presents itself. But this time, all my ideas seemed irrelevant in light of the anxiety and suffering engendered not only by the pandemic, but by the killing of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Rayshard Brooks.

Still, I had to get back on the horse. As much as I enjoyed making yogurt from scratch and growing basil from seed, I was getting cranky. I hadn’t written anything in weeks, then months. Finally a workable idea started circling in my head—right around the time my husband went to the hospital for an angiogram. We thought he might get a stent or two, but the doctors said he needed surgery—immediately. His arteries were so blocked, they were afraid to send him home. Five bypasses and six days later, he left the hospital.

Now that Tom is getting his energy back and walking up to an hour a day, I can focus.

Everybody is spending a lot more time at home, so I thought I’d tell you a little bit about the Bowen approach to understanding how families work. The cool thing is that it teaches you how to observe interactions between family members, (including yourself), which helps to temper knee-jerk reactions with a more thoughtful response. It’s a very down-to-earth approach that has helped Tom and me a lot.

Over decades of observation, Murray Bowen, M.D., identified seven ways that family members relate to each other when anxiety runs high:

1. they bring in another person—a friend, rabbi, counselor, cop (triangling)

2. they fuse with each other, blurring their personal boundaries (fusion)

3. they fight a lot (conflict)

4. they separate, either psychologically or geographically or both (distance)

5. they cease all communication (cut-off)

6. one spouse overfunctions, the other underfunctions (over-/underfunctioning reciprocity)

7. they focus their anxiety on a child (dysfunctional child)

Everybody’s been in a triangle. A simple example is when you’re mad at a friend. Instead of talking to the friend, you unload on someone else. Triangles arise between friends, between parents and children, and between spouses and a third party.

When I left for Africa in 1979, I was caught in a triangle between my divorced parents, which is part of the reason I went away. When entrenched, a relationship triangle can put you in lockdown even more than a pandemic. More about this next time—until then, maybe you’d like to look at some of the relationship triangles in your own life.